Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome

What is hypoplastic left heart syndrome?

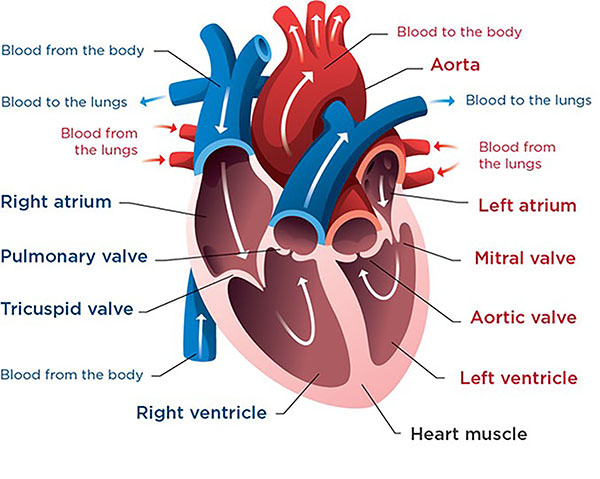

This is a healthy heart. The right ventricle pumps oxygen-poor blood to the lungs. The left ventricle pumps oxygen-rich blood through the aorta to the rest of the body.

This is a healthy heart. The right ventricle pumps oxygen-poor blood to the lungs. The left ventricle pumps oxygen-rich blood through the aorta to the rest of the body.

Hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) is when the left side of the heart is not fully developed. It is a serious birth defect. Babies with HLHS need medical care as soon as they are born.

A healthy heart works this way:

- Oxygen-poor (blue) blood comes from the organs and tissues of the body into the right atrium of the heart. Then the tricuspid valve opens, letting blood flow into the right ventricle. Next, the pulmonary valve opens, and the right ventricle pumps blood to the lungs.

- Oxygen-rich (red) blood comes from the lungs into the left atrium. Then the mitral valve opens, letting blood flow into the left ventricle. Next, the aortic valve opens, and the left ventricle pumps blood through the aorta and out to the rest of the body.

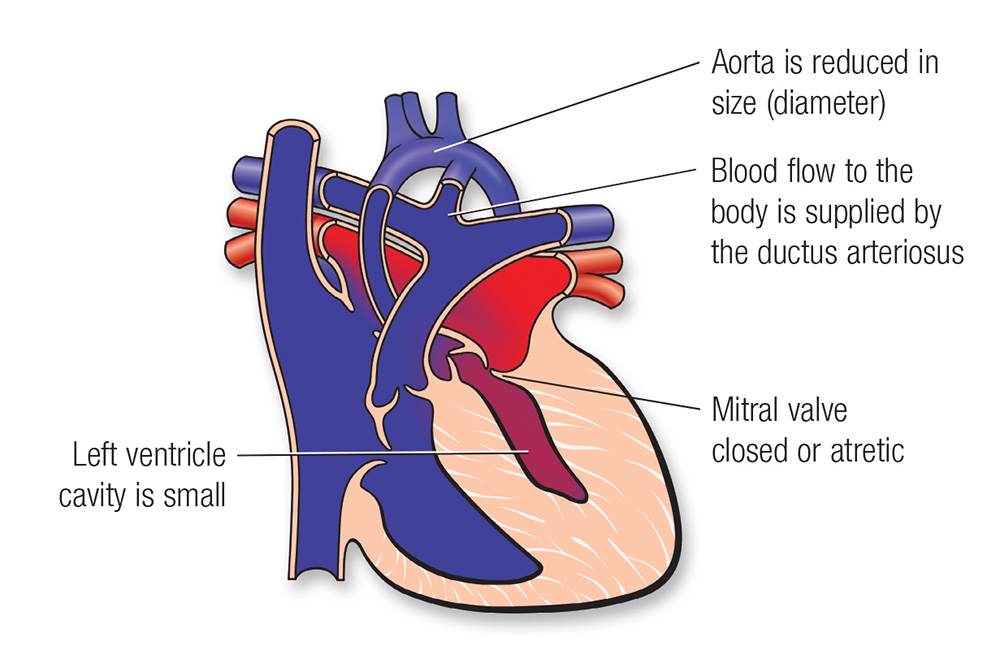

In a child with HLHS:

- The mitral valve is small or missing.

- The left ventricle is very small (hypoplastic) and cannot pump well.

- The aortic valve is small or completely closed.

Several other heart conditions are called hypoplastic left heart syndrome variants. They cause similar problems and have similar treatment plans.

About 1 in every 4,000 babies has HLHS. Doctors consider it a rare heart defect.

This is a heart with HLHS. From heart.org. ©2009, American Heart Association, Inc.

This is a heart with HLHS. From heart.org. ©2009, American Heart Association, Inc.

-

What are the effects of HLHS?

Because the left ventricle cannot pump enough blood to the body, the right ventricle must do all the work.

In a newborn, this can work for a short time. Newborns have an opening between their right and left atria (foramen ovale) and a blood vessel from their pulmonary artery to their aorta (ductus arteriosus).

The foramen ovale lets both oxygen-rich blood from the lungs and oxygen-poor blood from the body enter the right side of the heart. The right ventricle then pumps this mixed-oxygen (purple) blood to the lungs and to the body through the ductus arteriosus.

Normally, the foramen ovale and ductus arteriosus close soon after birth. If they close in a baby with HLHS, little or no blood can flow through their heart to their body.

The other risk for babies with this syndrome is that their right ventricle must do so much work. Over time, this can cause heart failure.

Heart Center at Seattle Children's

What are the symptoms of hypoplastic left heart syndrome?

Most babies with HLHS develop symptoms within the first days after birth if they do not get the medical care they need.

Common symptoms include:

- Blue or purple-tinged skin, lips or fingernails (cyanosis) or skin that looks mottled, grayish or paler than your baby’s usual skin color

- Being more tired than is normal

- Trouble feeding

- Fast breathing or working hard to breathe

- Cold arms and legs

- Weak pulse

How is hypoplastic left heart syndrome diagnosed?

-

Fetal diagnosis

Usually, doctors can diagnose HLHS when a baby is in the womb using a fetal echocardiogram (fetal echo). This is a special ultrasound that uses sound waves to view and make pictures of a developing baby’s heart during pregnancy. The results are interpreted by a pediatric heart doctor (cardiologist) who specializes in fetal congenital heart disease.

Your obstetrician may refer you for a fetal echo if your family has a history of congenital heart disease or if a routine prenatal ultrasound shows a problem.

Seattle Children’s Fetal Care and Treatment Center team can care for you when you are pregnant if your developing baby has a known or suspected problem.

-

Diagnosis in newborns

To diagnose this condition, your child’s doctor will examine your baby, check their heartbeat and pulse and listen to their heart.

The doctor will ask for details about your child’s symptoms, their health history and your family health history.

Your child will need tests that provide more information about how their heart looks and works. These may include:

- Electrocardiography

- Echocardiography

- Chest X-rays

- Cardiac catheterization

- Pulse oximetry

How is hypoplastic left heart syndrome treated?

Babies with HLHS need surgery in the first weeks of life. They get a series of surgeries to change blood flow through their heart.

Before surgery, your baby will need medicine (prostaglandin) that keeps the ductus arteriosus open so blood can get to the rest of their body. Your baby may need help breathing or need to be on a breathing machine (ventilator).

HLHS is called a “single-ventricle heart defect” because there is only 1 pumping chamber in the heart, instead of the usual 2. Single-ventricle defects are some of the most complex heart birth defects. We provide comprehensive care for children with HLHS through our Single Ventricle Program.

Surgery

Surgery for HLHS does not give babies normal blood flow. But it may allow their heart to pump blood better to their lungs and the rest of their body.

The surgery is done in 3 stages during the first few years of life:

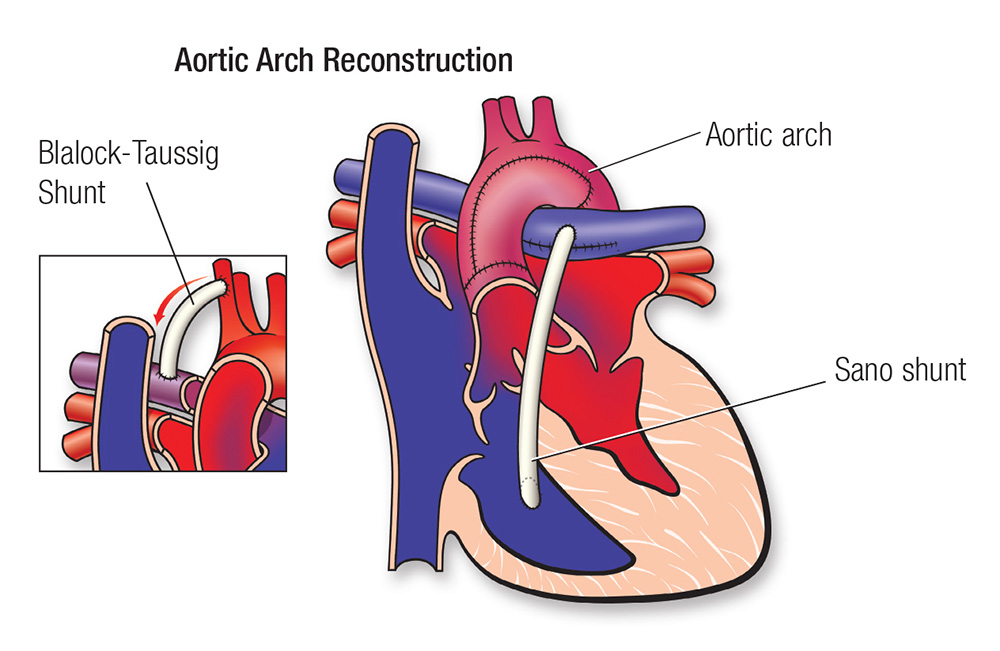

- The first stage is the Norwood procedure. It is usually done in the first weeks of life and is the most complex.

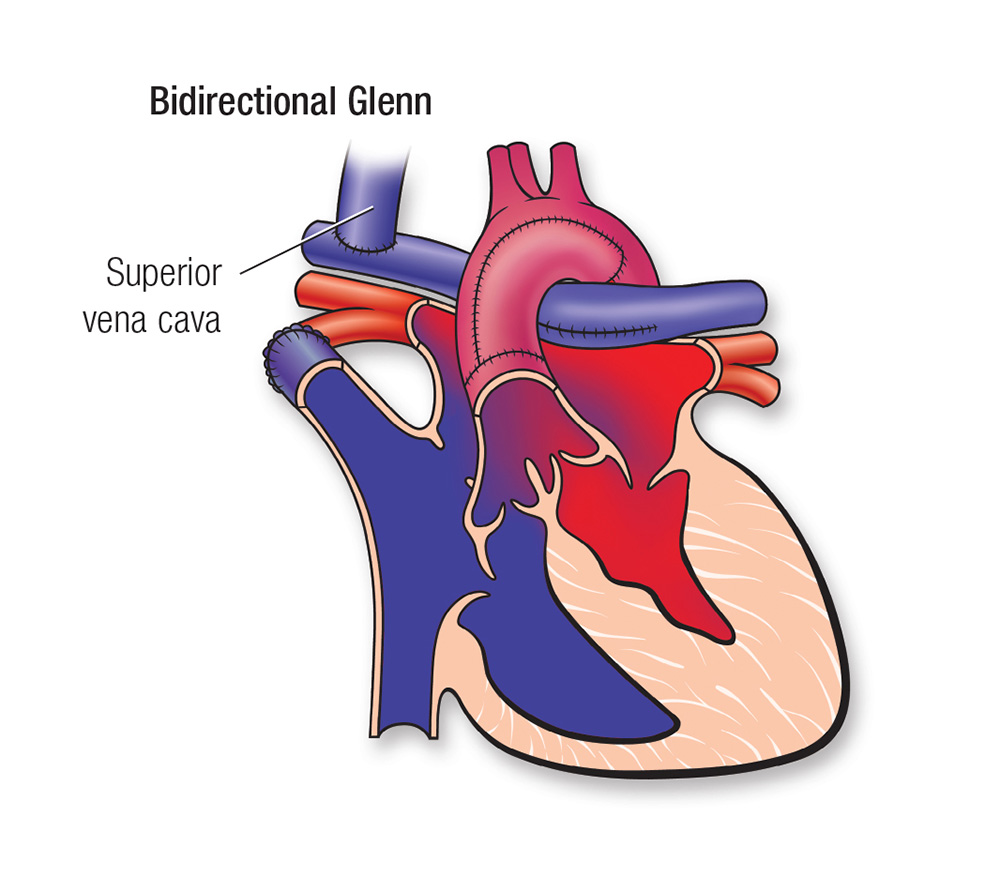

- The second stage is the Glenn operation. It is usually done between 3 and 6 months of age.

- The last stage is the Fontan procedure. It is usually done around 3 to 5 years of age.

The exact procedures and timing depend on your child’s condition, including how severe it is. After your child has a Fontan procedure, they get coordinated, ongoing, team-based care through our Fontan Clinic.

-

Stage 1: Norwood procedure

From heart.org. ©2009, American Heart Association, Inc.

From heart.org. ©2009, American Heart Association, Inc.Surgeons turn the right ventricle into the main pumping chamber and make the aorta larger. A synthetic tube, called a Sano shunt, brings blood from the ventricle to the lung arteries. A large hole is made between the two atria so blood can pass easily between them.

-

Stage 2: Bidirectional Glenn operation

From heart.org. ©2009, American Heart Association, Inc.

From heart.org. ©2009, American Heart Association, Inc.The superior vena cava is a vein that drains blood from the arms and head. In the Glenn operation, surgeons connect this vein to the pulmonary arteries and they remove the Sano shunt.

-

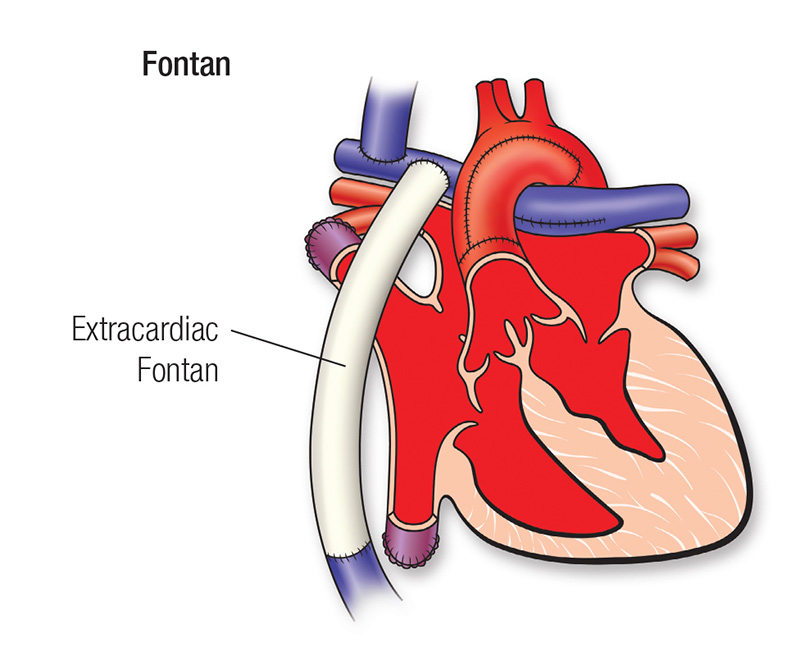

Stage 3: Fontan operation

From heart.org. ©2009, American Heart Association, Inc.

From heart.org. ©2009, American Heart Association, Inc.A synthetic tube is used to bring blood from the lower body to the lungs without going through the heart. After this surgery, the blood pumped to the body has normal oxygen levels.

The goals of the surgeries are:

- To make a new aorta that can carry enough blood out to the body and to connect this aorta to the right ventricle.

- To separate oxygen-rich blood from oxygen-poor blood in these ways:

- Direct oxygen-poor blood, which comes from the organs and tissues of your child’s body, to blood vessels that go to their lungs, without going into their heart first. The blood picks up oxygen in the lungs.

- Allow oxygen-rich blood, which comes from your child’s lungs, to flow into their right ventricle. From there, the heart can pump this blood to the rest of their body.

Hybrid procedures

Some newborns may be too small or have other health problems that increase the risk of the first-stage surgery (Norwood procedure) for HLHS. A less complex option, called a hybrid procedure, combines surgery and cardiac catheterization.

Using a catheter, a heart doctor (cardiologist) widens the foramen ovale and places a stent in the ductus arteriosus to keep it open. (Learn more about patent ductus arteriosus stenting.) Then a cardiac surgeon places bands on the pulmonary arteries to control the amount of blood flowing to the lungs. This approach lets the baby grow and get stronger. During the second stage, the Norwood and Glenn surgeries can be done together at 4 to 8 months of age.

Transplant

Some children need a heart transplant. The heart transplant team at Seattle Children’s does many transplants each year for children with HLHS or other heart problems that cannot be treated with standard medical or surgical treatment. Read more about our Heart Transplant Program and our exceptional outcomes.

Follow-up care

Outcomes for children with HLHS have improved greatly in the past several decades. Still, these babies are quite vulnerable between their first and second surgeries. They are at risk for serious health problems from common childhood illnesses, like colds, and they may have trouble feeding and growing. To provide complete care and closely check babies with HLHS, we see them through our Single Ventricle Program.

Why choose Seattle Children’s for hypoplastic left heart syndrome treatment?

-

The experts you need are here

- The Heart Center team includes more than 40 pediatric cardiologists who diagnose and treat every kind of heart problem. We have treated many babies with this condition.

- Our doctors and surgeons have deep experience with the treatments your child may need. These may include surgery to change blood flow in your child’s heart, hybrid procedures and a heart transplant.

- Our 4 pediatric cardiac surgeons perform more than 500 procedures yearly. Our surgical outcomes are among the best in the nation year after year. See our outcomes for surgeries done for single-ventricle defects.

- We also have a pediatric cardiac anesthesia team and a Cardiac Intensive Care Unit ready to care for children who have heart surgery.

- Children with HLHS receive compassionate, comprehensive care through Seattle Children’s Single Ventricle Program. We bring together specialists in cardiology, nutrition, social work, feeding therapy and neurodevelopment to support your child’s health between surgeries.

- The transplant team does several heart transplants each year for children with HLHS or other heart problems that cannot be controlled using other treatments.

- Your child’s team includes other experts from Seattle Children’s based on their needs, like doctors who specialize in newborns (neonatologists) or lung health (pulmonologists).

-

Care from fetal diagnosis through young adulthood

- If your developing baby is diagnosed with HLHS before birth, our Fetal Care and Treatment Center team works closely with you and your family to plan and prepare for any care your baby may need.

- Your child’s treatment plan is custom-made. We plan and carry out their treatment based on the specific details of their heart defect. We closely check your child’s needs to make sure they get the care that is right for them at every age.

- We have a special Adult Congenital Heart Disease Program to meet your child’s long-term healthcare needs. This program, shared with the University of Washington, transitions your child to adult care when they are ready.

-

Support for your whole family

- We are committed to your child’s overall health and well-being and to helping your child live a full and active life.

- Whatever types of care your child needs, we will help your family through this experience. We will discuss your child’s condition and treatment options in ways you understand and involve you in every decision.

- Our Child Life specialists know how to help children understand their illnesses and treatments in ways that make sense for their age.

- Seattle Children’s has many resources, from financial to spiritual, to support your child and your family and make the journey as smooth as possible.

- Many children and families travel to Seattle Children’s for heart surgery or other care. We help you coordinate travel and housing so you can stay focused on your child.

- Read more about the supportive care we offer.

-

Advancing treatment for children

- Seattle Children’s is part of a nationwide group of children’s hospitals called the National Pediatric Cardiology Quality Improvement Collaborative (NPC-QIC). This group works to improve the outcomes and quality of life for children with HLHS. The NPC-QIC also offers resources, support and information for families.

Emma had her first surgery for hypoplastic left heart syndrome just a week after she was born. Watch her mom, Cindy, talk about getting through those early days. (Video. 2:11)

Contact Us

Contact the Heart Center at 206-987-2515 for an appointment, second opinion or more information.

Providers, see how to refer a patient.

Related Links

- Heart Center

- Heart Center Team

- How to Handle a Difficult Prenatal Diagnosis

- What to Expect: Heart Surgery

Paying for Care

Learn about paying for care at Seattle Children’s, including insurance coverage, billing and financial assistance.