Revolutionary New Surgery for Complex Craniosynostosis

A revolutionary new surgery changes the picture for children with Apert syndrome.

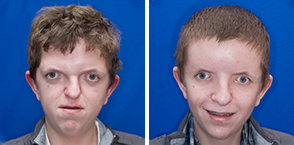

A distractor, also called a “halo,” moves the middle of James Weatherwax’s face forward slowly over several weeks. James was born with Apert syndrome, a genetic disorder that prevents the bones in a child’s skull and face from growing normally, and can make it difficult for kids like him to do everyday things like breathe, eat, talk or sleep.

A distractor, also called a “halo,” moves the middle of James Weatherwax’s face forward slowly over several weeks. James was born with Apert syndrome, a genetic disorder that prevents the bones in a child’s skull and face from growing normally, and can make it difficult for kids like him to do everyday things like breathe, eat, talk or sleep.If we’re born with the expected configuration of features, we can afford to take our faces for granted. Although we might wish for a smaller nose or movie-star cheekbones, our faces will do.

But children born with Apert syndrome don’t have that luxury. Their faces get in the way of simply breathing, eating and sleeping.

Apert syndrome is a rare and extreme form of craniosynostosis, where one or more of the special joints between the bones of the skull, called sutures, fuse before birth – years too early – deforming the head and putting pressure on the brain.

Because the bones in the center of their faces are jammed together like a compressed jigsaw puzzle, children with Apert syndrome have concave faces; bulging eyes; a small, beaked nose; and an undersized upper jaw. Their fingers and toes are often fused together. They likely have severe sleep apnea, and can suffer hearing loss, dental problems and developmental delays.

Face is portal to the world

The difficulties of Apert syndrome go beyond the physical challenges, says Dr. Richard Hopper, a craniofacial surgeon who is revolutionizing the surgical options for kids with the syndrome.

“We love James whatever he looks like, but I had to do this to improve his quality of life.”

“We interact through our faces; it’s our portal to the world. Imagine a child whose face constantly lets them down. They can’t breathe. Their eyes are watery. They’re drooling. Their teeth don’t fit together. They talk funny. Their face is always in the way of what they want to do.

“And as humans we instinctively scan a person’s face when we meet them. If the proportions and balance of the face look right, we’re more likely to interact,” says Hopper. “When someone meets a child with Apert syndrome for the first time, it can be hard for the person to get past the fact that the child’s face just looks wrong.”

James’ journey

James has been treated at Children’s since he was a baby and has had more than 15 surgeries. Ongoing relationships like these are a big part of what motivates Dr. Richard Hopper to continue improving care.

James Weatherwax knows these challenges all too well. He was born with Apert syndrome and cleft lip and palate. He and his mom, Kecia Weatherwax, have been making the long journey from their island community in Klawock, Alaska, to Seattle Children’s since he was a baby. Now 10, James has already had more than 15 surgeries on his skull, face, hands and feet.

Weatherwax says that over the years she’s worried about how James would be accepted by others. People in their home community know and accept her son, but this hasn’t always been the case.

“There were times where kids have been cruel. People can just be really mean because they don’t understand him,” she says.

Reassembling the puzzle

Traditional surgeries for Apert and other syndromic forms of craniosynostosis move the facial bones together as one block, the same distance and in one direction. While it’s effective in helping kids breathe, that approach doesn’t normalize facial proportions. Hopper felt his patients deserved more.

So, over the past five years, he and his colleagues in the Craniofacial Center developed a new approach called segmental subcranial distraction. It combines existing techniques in a way that hasn’t been done before, and gives patients the benefit of multiple procedures in one surgery. It also does more than alleviate breathing and chewing problems: by normalizing the features, it gives a child with Apert syndrome the chance to interact socially without his face getting in the way.

“You need to move different parts of the face in different directions, and different distances,” explains Hopper. “Essentially, you have to unlock the compressed jigsaw puzzle and then reassemble it.”

During the delicate, daylong surgery, Hopper and his team separate the bones of the face from the skull, releasing the cheekbones and eye sockets from the middle of the face and repositioning them with small plates and screws. Using an implant that he and his colleagues design specifically for the child, he brings the forehead forward and attaches a device known as a distractor to the central part of the face.

While the child is recovering at home, a parent turns the distractor a millimeter a day for about two weeks to continually move the bones. New bone grows and fills in the gaps. Once everything is in the right place, the distractor stays on for about six more weeks while the bone solidifies.

Like James, Dino Velagic, 17, has Apert syndrome, and struggled to breathe until Hopper and his team performed a revolutionary new procedure called segmental subcranial distraction. This procedure, developed by Hopper, has only been done seven times – all at Seattle Children’s.

Transformative innovations like segmental subcranial distraction are only possible, Hopper says, because of the depth and range of skills in Children’s Craniofacial Center, the largest in the United States

Dr. Hitesh Kapadia, one of just a few craniofacial surgical orthodontists in the country, is a key collaborator. Weeks and even months before the surgery, he uses computer imaging and standardized growth predictions to precisely plan the direction and magnitude of the movement of the facial bones. Kapadia must take into account the age of the child at the time of surgery and accurately predict where the teeth need to meet, and how that affects the cheekbones, nose and the soft tissues of the face.

“You need to move different parts of the face in different directions, and different distances.”

Quality of life

Social worker Cassandra Aspinall collaborates with child life specialists to help children work through their anxiety. Depending on the child’s age and developmental needs, they may use tools like this doll fitted with its own custom-made halo.

Weatherwax initially hesitated when she heard about the new treatment. “We love James whatever he looks like, but I had to do this to improve his quality of life,” she says. Early in 2013, they made another trip to Seattle Children’s.

“He is doing really well now and is just being a happy boy who is always on the go,” says Weatherwax. “He goes out to play with his friends and he loves playing basketball and swimming. He is much more active and a lot more independent.”

For Hopper, that’s the measure of success. “For me, it’s never about ‘We moved that bone into a better position, wasn’t that a great surgery?’ It’s got to be, ‘Was that the best way to move that bone? How does that affect the child at 2 o’clock in the morning? How does it affect him when he meets a friend for the first time on the playground?’”

Giving Families Options

After endoscopic surgery, Wesley Matthes wore a custom helmet for eight months to reshape his head. “He slept fine with it from day one,” recalls his mother, Angela Neeleman. “Helmet therapy was worlds easier than I expected it to be.”

As Angela Neeleman and Steve Matthes discovered when their son Wesley was born, single-suture craniosynostosis (where just one of the skull joints fuses prematurely) can happen in any family. In fact, one in every 2,000 babies born each year has the condition.

The standard treatment involves a surgery with a large incision to remove the fused suture and reshape the skull bones; absorbable plates and screws hold the pieces in place while they heal.

Recently, Seattle Children’s has given families another option: a camera-assisted operation called endoscopic strip craniectomy. It uses two small incisions, takes half as long as the open surgery, and rarely requires a blood transfusion (which is almost guaranteed with the open method).

After the endoscopic surgery the baby must wear a helmet 23 hours a day for up to a year to mold the skull, and the family has to be able to come back frequently to get the helmet adjusted. (The helmet is similar to one originally developed at Children’s for babies who develop “flat head syndrome” from lying on their backs.)

“We’re confident both surgeries work equally well so families can choose the option that makes the most sense for them,” says Dr. Amy Lee, the neurosurgeon who brought the procedure to Children’s.

Neeleman was uneasy with the open surgery and appreciated having a choice about Wesley's treatment. “I’m his mom; my job is to protect him as best as I can from as many things as possible. The endoscopic option allowed me to do that.”

Published in Connection magazine, November 2013