Changing the Trajectory

Published in Connection magazine, Spring 2019

An intensive program gives young kids who are significantly impacted by autism the skills they need to engage with life.

Nataly Cuzcueta knew something wasn’t right with her twins, Kira and Aliya. At 11½ months they started to regress, as if a genetic switch had been flipped. Only two weeks before the concerning behavior started, the house had been filled with babbling and the unsteady pitter patter of toddling feet. Suddenly, it was eerily quiet as the girls reverted to crawling, no longer used their voices or made eye contact.

When Cuzcueta consulted their pediatrician, he reluctantly referred the twins to a state-sponsored Birth-to-Three program. There, the girls received services for developmental delays caused by their premature birth, but no one ever mentioned that they might be on the autism spectrum. Feeling alone and overwhelmed by their increasingly intense behaviors – epic tantrums, head banging, and the rigid rejection of anything new or different – she called Seattle Children’s Autism Center.

The Cuzcuetas’ story is all too familiar to Dr. Mendy Minjarez, the center’s clinical director. She says many families report feeling isolated and without clear guidance on where to go for answers before they visit the Autism Center.

“Imagine parenting a child you suspect may be on the spectrum, while at the same time trying to navigate multiple systems for services to figure out what’s really going on,” says Minjarez. “It’s a full-time job, and that doesn’t include fighting with your insurance carrier for coverage or appealing to federal and state agencies for support. I have a PhD and I’m not sure I could figure it all out as a parent!”

And accessing the right services is particularly difficult for low-income families. Many face additional challenges like limited English proficiency, lack of transportation and shaming cultural beliefs.

"I tell them you’re now part of our family at the Autism Center. You’re not alone. There’s support for you.” – Jaimie Sigesmund, case manager

A mandate for equity

Parent education is a critical part of the early intervention program (EIP). Liz Hatzenbuhler (left), EIP clinical supervisor, and Dr. Mendy Minjarez, the Autism Center’s clinical director and founder of the EIP, help parents perfect hands-on techniques to work more successfully with kids. They also teach parents about the services their children will need in the future and where to find those resources in the community.

In 2011, a Washington state court ordered Medicaid to cover Applied Behavioral Analysis (ABA), a type if autism therapy with proven successful outcomes. The court also ordered Medicaid to build a provider network to deliver that therapy. The insurance giant approached Seattle Children’s – and Minjarez – for help.

“Although ABA is typically a longterm therapy, I jumped at the chance to develop a short-term ABA program where we could intervene earlier in kids’ lives when their brains are more malleable,” explains Minjarez. “Plus, we made sure the guidelines we developed could be replicated statewide to ensure as many children as possible would be exposed to this type of therapy.” To date, the program has been successfully implemented more than 15 times in cities including Spokane, Yakima, Longview, Tri-Cities, Moses Lake and Bellingham.

Minjarez, who leads the program and trains providers across the state, calls the intensive 12-week treatment the early intervention program (EIP). It offers the resources needed to get children up to age 6 ready to take their next steps in the community – like entering daycare, school or a long-term ABA program. Depending on the child, this could include developing communication skills, reducing behavioral problems or completing toilet training.

Since the program’s inception in 2015, three out of every four children have started with no functional communication; by the end of each three-month session, almost all of the children who began with no ability to communicate graduate with the ability to get a caregiver’s attention and request objects or help.

The training component for parents is equally noteworthy. Parents gain skills to work more successfully with their kids, including learning what services they need and how to find them. During the last three years, more than 100 families have completed the program.

Michelle Rodelo credits the EIP with saving her sanity. Her son, Sam Bass, was born prematurely at 26 weeks and weighed just two pounds. When the family finally brought him home from the hospital, Sam’s lack of reaction to everything – silly faces, sounds, other people – caused great concern. It wasn’t until Sam was 3 that a speech therapist at Seattle Children’s told Rodelo his quirky behavior wasn’t due to developmental delays and referred them to the Autism Center.

“This may sound crazy, but I was happy about the referral,” remembers Rodelo. “I knew there was something different about Sam, but I didn’t know what to call it. Once the center gave me words for his condition and I saw that they knew how to work with him, I was pretty excited to get started in the EIP.”

Life-changing approach

Stephanie Grillo, certified behavior technician, uses one-on-one play to work on important communication skills that Levi Eiger, 4, will need to be more successful in his interactions with others.

ABA isn’t a new therapy. Its focus on positive reinforcement was first applied to autism in the 1960s and 1970s. After a groundbreaking 1987 study, it became the go-to choice for autism spectrum disorder therapists who wanted to increase helpful behaviors like self-soothing, communication and interaction skills, and decrease problem areas like repetitive behaviors, rigid interests and self-harming.

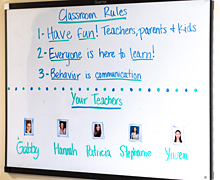

The EIP classroom is set up like a preschool, and Liz Hatzenbuhler and her team of behavior therapists give one-on-one attention to each child. The team’s success lies in their ability to closely observe each child and accurately determine why they engage in certain behaviors like tantrums or head-banging.

“By figuring out how a behavior serves a child, then we can develop an intervention plan,” says Hatzenbuhler. “That plan is different for every single child, and it includes knowing what will motivate them to choose different behaviors.”

The EIP team uses Applied Behavioral Analysis (ABA), a proven autism therapy that uses positive reinforcement to increase helpful behaviors like self-soothing, communication; and interaction skills and decrease problem actions like repetitive behaviors, rigid interests and self-harming.

For Sam, who cried every time he had to make a transition, that meant having tokens with pictures of his favorite Star Wars characters. If he engaged in a new activity for a couple of minutes without an outburst, he could stick a token onto a card. If he got five tokens on his card, he was allowed to play with one of his favorite toys – usually the firefighter dress up gear or the doctor instruments set – as a way to reinforce his newfound flexibility.

“I loved watching Sam’s teacher reshaping his rigidity,” says Rodelo. “She’d have Sam create a story and then they would act it out. Sam had to learn how to take turns and let the story change when it was her turn. It was amazing to see her lay on the floor with him and pretend to be an astronaut pushing buttons on a spaceship or a firefighter climbing ladders. What the ABA team does is definitely not guesswork. Now Sam will play whatever you want to play. His imagination grew and he’s excited to pretend.”

1 in 59 – Current rate of autism diagnoses in the U.S.

Extending the impact

Jaimie Sigesmund (left), EIP case manager and family advocate, extends the program’s impact by helping parents like Nataly Cuzcueta work through the non-clinical roadblocks of raising a child with autism, like identifying helpful resources in the community. While critical to the success of the EIP, Sigesmund’s role would not be possible without donor support since insurance doesn’t reimburse for her services.

Case management is one of the pillars of the EIP – a way to extend the program’s impact by meeting weekly with families to help them overcome social/emotional barriers outside of clinical services. For one parent, it may be connecting them with food or transportation services; for someone else, a shoulder to cry on; for yet another, a session practicing how to talk with a school administrator.

“I’m the first person families talk to when they’re interested in the program,” says Jaimie Sigesmund, EIP case manager. “l tell them you’re now part of our family at the Autism Center. You’re not alone. There’s support for you.”

She’s also the first person families call for advice after they’ve graduated. Rodelo says she’s “like Google but better” because of her encyclopedic knowledge of community resources. Sigesmund’s role is paid for by a patchwork of support from a Seattle Children’s fundraising guild, individual donors and community partners since insurance doesn’t reimburse for her services.

“Most of our parents come to us lost and vulnerable, like deer in the headlights,” Sigesmund reflects. “They truly blossom over the three-month EIP, and they leave empowered to advocate for services in the community that will help their kids thrive.”