Donors Propel Efforts to Develop Gene Therapy and Immunotherapy

We’re inserting new genetic instructions into cells to develop therapies that could cure diseases once and for all.

Published in Connection magazine, Spring 2017

Since her children Preston, (left) now 7, and Sophia, now 9, were diagnosed with type 1 diabetes, Julie Nguyen must track their blood sugar levels around the clock to manage the short- and long-term risks associated with their illness

Since her children Preston, (left) now 7, and Sophia, now 9, were diagnosed with type 1 diabetes, Julie Nguyen must track their blood sugar levels around the clock to manage the short- and long-term risks associated with their illness

Several times a night, Julie Nguyen wakes up and squints at the smart watch that tracks her children’s blood sugars. Sophia, 9, and Preston, 7, both have type 1 diabetes – if their blood sugar falls too low or climbs too high, they could have seizures or slip into a coma.

On a good night, their levels are normal. But most nights Nguyen has to walk into her kids’ bedrooms to deliver an insulin shot or stuff fruit snacks into their cheeks. Then she waits up to make sure their blood sugar gets back into the safe range.

It’s just one example of how Nguyen and her husband, Chris Miele, spend their lives on high alert, acutely aware that how well they manage Sophia and Preston’s diabetes affects their children’s long-term risk of stroke, heart disease and other serious health problems.

“My uncle had diabetes and had both legs partly amputated. My grandfather had it too. They both died much earlier than they should have,” Miele says. “I never stop worrying about what might happen to my kids.”

Researchers at Seattle Children’s are working toward a day when kids like Sophia and Preston won’t need lifelong treatment.

Living therapies

Researchers at Seattle Children’s are working toward a day when kids like Sophia and Preston won’t need lifelong treatment. Instead, they’ll get cell therapy – a single infusion of cells that cures their disease forever.

To create cell therapies, researchers remove a small number of cells from a patient’s blood. Then they change the genetic instructions in those cells and infuse them back into the patient.

“Sometimes, the new instructions tell the cells to fight back against disease,” says Dr. David Rawlings. “Other times, the instructions fix genetic mistakes that cause a disease, with the goal of curing it at the source.”

In our initial studies, these therapies have shown promise against leukemia and severe immune disorders. Now we want to invest big to speed up our progress and help our researchers pursue cell therapies for dozens of other diseases — from diabetes to HIV.

“In the past few decades, researchers have made tremendous progress on treatments that control diseases or their symptoms,” says Dr. F. Bruder Stapleton, Seattle Children’s chief academic officer. “The next step is to find cures.”

Redefining cancer therapy

The Cross family came to Seattle Children’s from Chester, England, so their daughter, Erin, could join our cancer immunotherapy clinical trials.

The Cross family came to Seattle Children’s from Chester, England, so their daughter, Erin, could join our cancer immunotherapy clinical trials.

Erin Cross’s leukemia relapsed last March. She was 5 years old and out of treatment options. Then her family, of Chester, England, heard that Seattle Children’s was studying a cell therapy called cancer immunotherapy.

This approach reprograms T cells by inserting genes that tell them to find and kill cancer cells. Dr. Michael Jensen’s team at the Ben Towne Center for Childhood Cancer Research develops these therapies, tests them in our labs and creates them in our special FDA-approved manufacturing facility.

Erin and her parents flew to Seattle to participate in our first immunotherapy clinical trial. The experimental treatment put her cancer into remission and helped her get healthy enough to undergo a bone marrow transplant that could cure her cancer once and for all.

“We’re so grateful for what this therapy did for Erin – and it’s amazing to think that immunotherapy for leukemia is just the beginning,” says her mom, Sarah Cross.

Now our researchers are developing ways to prevent relapse and designing immunotherapies for other more complicated cancers. We’re leading one of the nation’s first clinical trials of T-cell therapies for neuroblastoma.

“We have a long way to go, but we’re getting the first glimpse of a therapy that could wipe out cancer and be far less toxic than today’s treatments,” says Dr. Jim Hendricks, president of Seattle Children’s Research Institute. “We want to replicate that progress for many other cancers and diseases.”

Fixing faulty genes

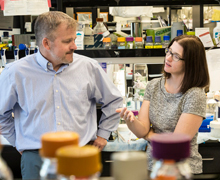

Drs. Michael Jensen and Rebecca Gardner are creating and testing immunotherapies that use a child’s immune cells to find and kill cancer cells.

Drs. Michael Jensen and Rebecca Gardner are creating and testing immunotherapies that use a child’s immune cells to find and kill cancer cells.

When Rawlings started his career in the 1990s, he saw infants who were unable to fight infections and kids whose immune systems attacked their bodies from the inside out.

“I knew some of those children would die because there were no good treatments,” Rawlings says. “And when we did have treatments, they only addressed the symptoms, had long-term side effects and sometimes just stopped working.”

He and his research partner, Dr. Andy Scharenberg, have spent years pioneering a cell therapy technique called gene editing, which aims to fix or replace the genes that cause disease.

“Some diseases are caused by a spelling error in the DNA, which is like a mistake in the instructions that tell your body how to function,” Scharenberg says. “We’ve developed technology that can edit those spelling errors to hopefully stop diseases in their tracks.”

Rawlings and Scharenberg recently opened a clinical trial of a genetic treatment for a life-threatening condition called severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID). Children with SCID are born without an immune system and the only cure is to undergo a bone marrow transplant. Our treatment might be able to cure the disease without a transplant, by replacing the faulty gene.

Rawlings plans to open similar trials within two years for two other rare immune diseases, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome and X-linked agammaglobulinemia.

Stopping “attacker” cells Rawlings and Scharenberg are also developing cell therapies for autoimmune diseases, which strike when immune cells turn against the body and attack it. The researchers are using gene editing to generate a T cell that functions as a peacekeeper, telling attacker cells to calm down.

Rawlings and Scharenberg have used this approach to stop autoimmune disease in animals. They plan to start clinical trials for children within three years, beginning with rare diseases for which there are no effective treatments.

“The first step is to show these therapies are safe and effective for diseases that can’t be stopped any other way,” Rawlings says.

The long-term goal is to use cell therapies to replace today’s treatments for diseases like lupus and diabetes, potentially freeing kids like Preston and Sophia from lifelong treatment.

Your support can help us apply gene editing to more genetic diseases and transform the lives of even more children and the families who love them.

Local work, global impact

Cancer and immune disorders are only the beginning. Our researchers are also working toward cell therapies that could cure everything from HIV to malaria, and stop kids’ bodies from rejecting transplanted organs. But our current facilities can’t accommodate all the clinical trials we have in the pipeline.

That’s one reason why we broke ground in February on Seattle Children’s Research Institute: Building Cure, a state-of-the-art research facility that will help us carry out our cell therapy push. At 540,000 square feet, it will double our research space, giving us room to recruit more all-star researchers and to build a new state-of-the-art lab to make cell therapies.

“The manufacturing facility is going to be a game changer because it will give us the capacity to produce these therapies on a large scale, so we can run clinical trials that show us if they’re effective and how to improve them,” Rawlings says.

Hendricks envisions Building Cure becoming the epicenter of cell therapies that cure children worldwide.

“I hope that, someday, doctors will send us cells from children who are born with an immune disorder or diagnosed with cancer. We’ll edit or reprogram those cells and send them back,” Hendricks says. “This is about more than just finding cures for kids in Seattle – it’s about transforming treatment around the world.”

Support Our Work

Your support makes it possible for us to investigate cell therapies that target diabetes and other life-altering diseases. You can learn more by contacting Andrew Welch.